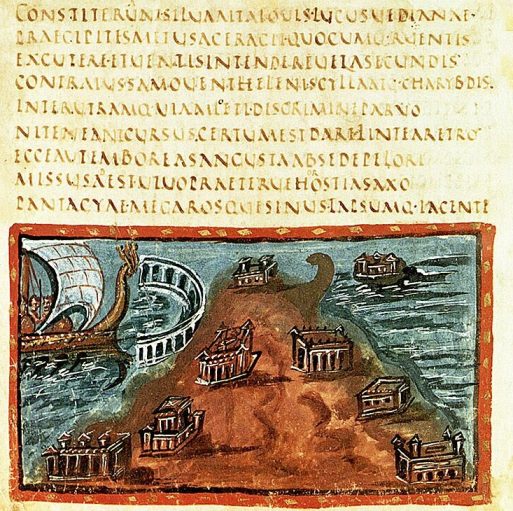

Folium 31 (Aeneid 3.692–708) of the Vergilius Vaticanus (Vatican Library, Vat. lat. 3225). Dating from around 400 CE, it is one of the oldest surviving manuscripts of Virgil’s works.

By Francisco Anania

When reading classical works, it is useful to understand the role of textual criticism. No original manuscripts from Greek or Latin literature have survived; instead, what we read today are texts transmitted through numerous copies made across centuries. Often these copies are partial or incomplete, altered through citations, paraphrases, or even copying errors. This transmission generally occurs in two main forms:

• Direct tradition: Manuscripts that preserve the text directly.

• Indirect tradition: Texts preserved through quotations or paraphrases in later writings, such as scholarly commentaries or historical references, often found in papyri or manuscripts.

Textual Criticism

Textual criticism is the scholarly discipline dedicated to studying this textual transmission. Its primary aim is to reconstruct a text as accurately as possible, reflecting the author’s original intent. To achieve this, textual critics carefully examine existing manuscripts (“witnesses”) and attempt to identify lost intermediate copies that shaped the surviving texts. However, before texts even reached this stage, they underwent a significant process of loss, often influenced by changing tastes, educational priorities, and the availability of copies. This process could have radical results: for instance, of the approximately 1,700 tragedies performed in Athens during the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, only 31 survive today; of around 600 comedies from the same era, only 11 remain complete, all of them by Aristophanes. The preservation of literature from later periods, such as Menander’s Dyskolos, was an even more hit-and-miss affair.

Shifts in literary tastes, educational decisions, and cultural identity had a major influence on which texts survived. Works admired by successive generations were regularly copied and preserved, while texts that fell out of favour often disappeared entirely. Attempts to reconstruct a cultural identity reflect other influences; the Atticising fashion of the Roman Empire’s second century CE (known as the Second Sophistic), for example, was heavily reliant on the passionate study and imitation of classical Greek models. This could favour the survival of some texts while simultaneously leading to the neglect and eventual loss of non-classical, especially Hellenistic, prose.

Additionally, random and unpredictable factors played a crucial role. Notable catastrophic events contributed significantly to the loss of classical literature. Examples include the burning of the Library of Alexandria, which held around 700,000 volumes, during Caesar’s siege in 48 BCE; the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 CE when 1,800 or more scrolls belonging to the library at the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum were carbonised; and the destruction of the public library at the Porticus Octaviae in Rome in 80 CE. Further immense losses occurred during the infamous Fourth Crusade in the 13th century CE, when Christian crusaders devastated Constantinople, destroying priceless manuscripts and treasures, a catastrophe compounded by the Ottoman conquest in 1453.

Several important terms help us understand the intricate process of reconstructing a text:

• Exemplar: The manuscript from which a scribe produced a copy.

• Copy: The manuscript resulting from the copying process, typically containing unintentional mistakes or deliberate alterations by scribes.

The Archetype

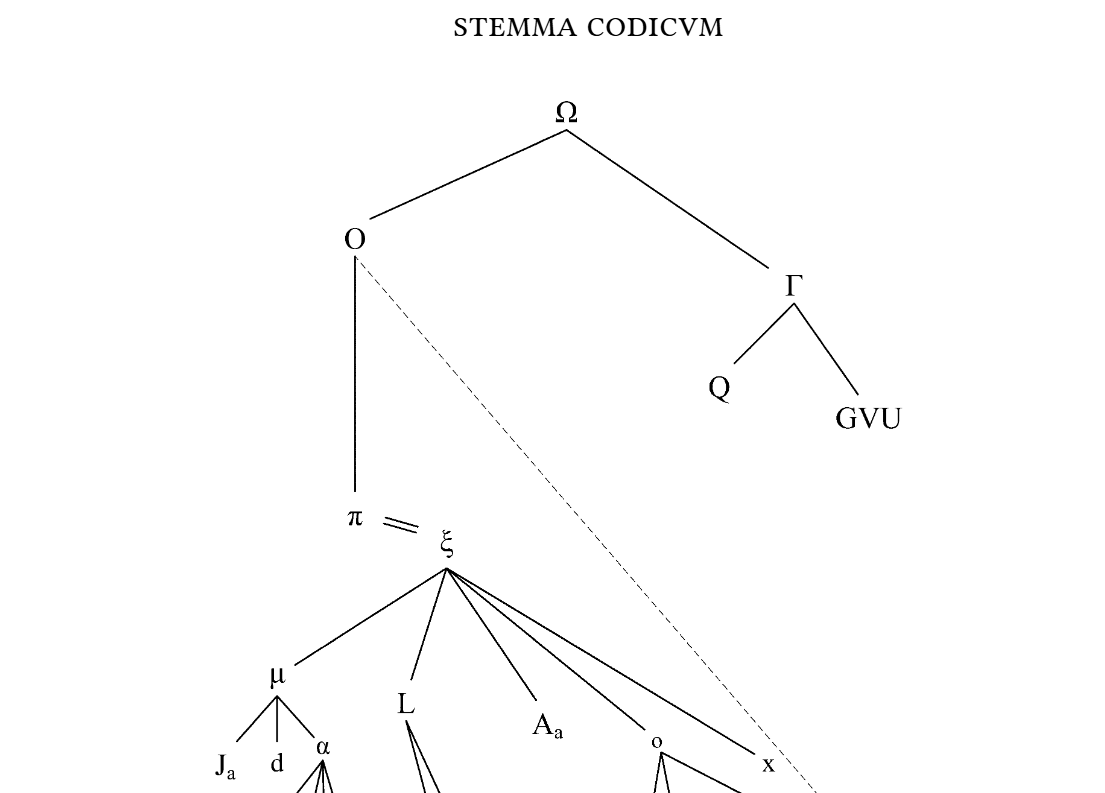

Detail from the stemma codicum of Lucretius’ De rerum Natura (edition by Marcus Deufert, De Gryuter, 2019). Greek letters represent hypothetical versions; Latin letters, extant witnesses. Ω represents the archetype.

Central to textual reconstruction is the concept of the archetype—the earliest form of a text that can be reliably reconstructed through surviving manuscripts. Usually dating back to the 9th or 10th century, the archetype is not the author’s original manuscript but rather the earliest construable source from which later copies might have derived.

The methodological approach known as stemmatics, developed systematically by Karl Lachmann in the 19th century, plays a vital role in textual criticism research. Stemmatics maps the genealogical relationships among manuscripts, organizing them into a structured diagram known as a stemma codicum, similar to a family tree. By examining these relationships, textual critics can distinguish shared errors and original readings, greatly aiding the reconstruction of the archetype.

Stemmatics involves three primary stages:

• Recensio: The initial phase involves collecting, cataloging, and systematically classifying all known textual witnesses. This step creates the foundation for textual analysis.

• Examinatio: Textual critics closely examine and compare the variant readings across manuscripts. This comparative analysis allows scholars to determine the relationships among manuscripts and reconstruct the hypothetical archetype.

• Emendatio: In the final step, editors correct textual errors and inconsistencies. Such corrections are based on internal linguistic and stylistic evidence, applying scholarly judgment to restore what they believe most closely matches the author’s original wording.

Editors often use established principles to guide their decisions. One of these is the principle of usus scribendi, considering the author’s specific linguistic style and habitual expressions. Another important principle is the preference for the lectio difficilior, meaning the more difficult or unusual reading, on the assumption that simpler or clearer variants are likely to represent later simplifications or corrections introduced by scribes.

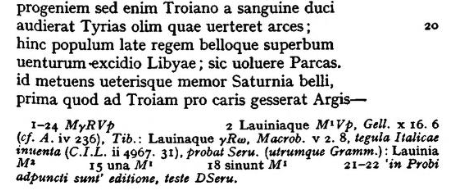

Critical editions are the published result of this meticulous work. They present the reconstructed text along with a detailed critical apparatus. Typically placed at the bottom of each page, this apparatus carefully documents alternative manuscript readings, editorial corrections, scholarly proposals, and textual uncertainties. By transparently showcasing this complex textual history, critical editions enable contemporary readers to engage deeply and authentically with ancient literature.

Critical apparatus showing the different readings or “variants” of the opening verses of the Aeneid (edition by R.A.B Mynors, OUP, 1969).

___________________________________________________

If you’re interested in exploring classical texts and learning to read them in their original languages, we encourage you to explore our range of Latin and Ancient Greek courses by visiting our courses page for more information and enrolment details.

___________________________________________________

Sources and Further Reading – Textual Criticism and History of the Tradition

AA.VV., Geschichte der Textüberlieferung der antiken und mittelalterlichen Literatur, I–II, Zürich 1961–64.

Alberti, G.B., Problemi di critica testuale, Firenze 1979.

Antonelli, R., “Interpretazione e critica del testo,” in Letteratura italiana, directed by A. Asor Rosa, vol. IV. 1, L’interpretazione, Torino 1985, pp. 141–243.

Brambilla Ageno, F., L’edizione critica dei testi volgari, Padova 1975.

Canfora, L., Conservazione e perdita dei classici, Padova 1974.

Cavallo, G. (ed.), Libri e lettori nel mondo bizantino. Guida storica e critica, Roma–Bari 1982.

Cavallo, G. (ed.), Libri, editori e pubblico nel mondo antico. Guida storica e critica, Roma–Bari 1984³.

Cavallo, G., Dalla parte del libro. Storie di trasmissione dei classici, Urbino 2002.

Fränkel, H., Noten zur Literaturkritik, Göttingen 1964.

Nesselrath, H.-G. (ed.), Einleitung in die griechische Philologie, Stuttgart–Leipzig 1997.

Maas, P., Textual Criticism, Oxford 1960⁴.

Mariotti, S., “Filologia classica,” in Enciclopedia Italiana, Appendice V, 1992, pp. 228–230.

Pasquali, G., Storia della tradizione e critica del testo, Firenze 1952².

Pfeiffer, R., Storia della filologia classica. Dalle origini all’età ellenistica, Napoli 1973.

Pöhlmann, E., Einführung in die Überlieferungsgeschichte und in die Textkritik der antiken Literatur, I. Altertum, Darmstadt 1994.

Reynolds, L.D., & Wilson, N.G., Scribes and Scholars, Oxford 1968.

Stoppelli, P. (ed.), Filologia dei testi a stampa, Bologna 1987.

Timpanaro, S., La genesi del metodo del Lachmann, Padova 1981².

Tosi, R., Studi sulla tradizione indiretta dei classici greci, Bologna 1988.